SOCIAL CHOICE How Nations (May) Decide on Distributions within Society

Publié le 21/08/2022

Extrait du document

«

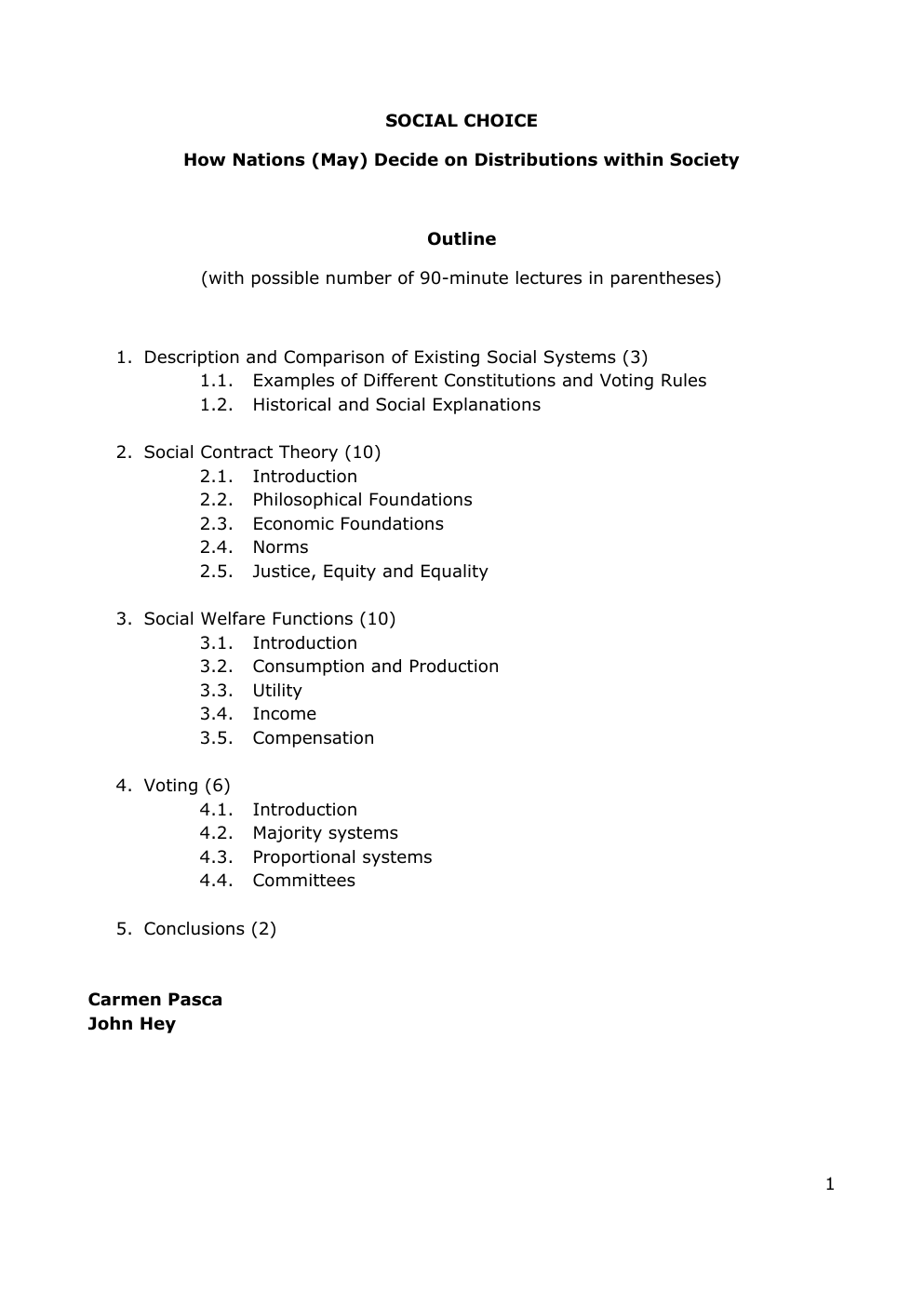

SOCIAL CHOICE

How Nations (May) Decide on Distributions within Society

Outline

(with possible number of 90-minute lectures in parentheses)

1.

Description and Comparison of Existing Social Systems (3)

1.1.

Examples of Different Constitutions and Voting Rules

1.2.

Historical and Social Explanations

2.

Social Contract Theory (10)

2.1.

Introduction

2.2.

Philosophical Foundations

2.3.

Economic Foundations

2.4.

Norms

2.5.

Justice, Equity and Equality

3.

Social Welfare Functions (10)

3.1.

Introduction

3.2.

Consumption and Production

3.3.

Utility

3.4.

Income

3.5.

Compensation

4.

Voting (6)

4.1.

4.2.

4.3.

4.4.

Introduction

Majority systems

Proportional systems

Committees

5.

Conclusions (2)

Carmen Pasca

John Hey

1

Preamble

The course as a whole is concerned with how societies choose, not only over political

and social issues but also over economic issues.

The course concentrates on the

economic implications of political and social decisions.

It begins with an overview of

different social systems and gives some historical background concerning the

evolution of the systems over time.

The course then goes on to consider the

philosophical considerations underlying considerations of the distribution of political,

social and economic power, before turning to more specifically economic

interpretations of these political concepts.

We discuss different formulations of social

welfare functions, through which policies can be compared before implementation.

Crucial to the actual operation of government is the way in which governments are

elected and the way in which decisions are implemented within government.

Such

issues concern the voting rules in society and in government.

As a whole, the course

provides an overview and analysis (descriptive, historical and theoretical) of the

principles lying behind social choice systems in the real world.

Detailed Structure

1.

Description and Comparison of Existing Social Systems

1.1.

Examples of Different Constitutions and Voting Rules

This section consists of a discussion of the main (constitutional and

unconstitutional) systems in operation throughout the world, with a

description of the structure of the constitution (and the rights and duties

of citizens) in the case of constitutional democracies and the implicit

rights and duties in non-constitutional systems.

For many years, the

political organization of states was founded on customs and traditions,

but their political legitimacy in the modern sense was virtually

nonexistent.

With the Enlightenment came the idea of popular

sovereignty; this caused a significant change of the political order.

The

foundation and the modalities of power were established.

This view of

popular sovereignty was formulated by the American colonies at the time

of their independence in the Preamble to the US Constitution of 1787.

The oldest written constitution is that of the U.S.

and is concerned with

the relationship between the central government and local authorities.

Some countries, like New Zealand, the United Kingdom and Israel, have

unwritten constitutions, based on morals.

The emergence of constitutions

has often been historically linked to periods of crisis: independence,

revolutions, coup d'etats, and serious political crises.

2.2.

Historical and Social Explanations

This sub-section gives a brief account of the evolution of the

constitutional and unconstitutional norms in society from a largely

2

historical perspective.

A good example is the case of France (see Gentile

(2005)).

As is evidenced by history, every new French republic has

brought a new constitution.

The original French Constitution was based

on a declaration of the rights of the individuals in society.

The French

Constitution today is based on the founding principles: political freedom,

equality between citizens, solidarity and brotherhood, the defence of the

weak and political and social progress.

2.

Social Contract Theory

2.1.

Introduction

It should be noted that the distinction between section 2 and section 3 is

somewhat blurred, as they both concern similar problems.

The distinction

that is made in this course is that section 2 is concerned more with

general philosophical principles while section 3 is more concerned with

practical (specifically economic) issues.

As Wikipedia notes “Social

contract theory describes a broad class of ...

theories whose subjects are

implied agreements by which people form nations and maintain a social

order.

Such social contracts imply that the people give up some rights to

a government and/or other authority in order to receive or jointly

preserve social order”.

This section concerns the kinds of agreements

that are made in different societies.

This first sub-section defines the

issues to be discussed and the framework in which they will be discussed.

2.2.

Philosophical Foundations

The core idea of Social Contract Theory concerns the moral and political

obligations of the state and of the citizens of that state.

Social Contract

Theory has its roots in the Greek philosophical tradition.

Plato and

Socrates stressed the importance of the relationship between the citizens

and the laws of the country.

Plato (see, for a translation into English

Bloom (1991)), in his dialogue La Repubblica, Plato (1992), explained the

nature of justice in the Social Contract.

According to Plato, justice, and

conventional laws and agreements, are there to prevent individuals

committing injustices against others.

Socrates gave greater importance

to the state in that it creates a Social Contract with the citizens of the

state: he argued that the state represents the fundamental political and

moral principles on which justice is based.

The modern idea of a Social

Contract dates back to Hobbes (for a modern commentary see Rogers

(1995)), Rawls (1971) and Rousseau (1968).

Hobbes based his theory of

a Social Contract on a hypothetical brutal State of Nature in which men

live in fear of their lives.

This State of Nature does not encourage

individuals to cooperate, nor does it guarantee long-term conservation

and the satisfaction of the citizens’ needs or desires.

He argued that

3

people are primarily self-interested but that a rational assessment of the

best strategy (to achieve the maximization of their self-interest) will lead

them to act morally (moral standards are determined by maximization of

mutual interest).

The existence of such a state is possible because men

are rational and recognize that the laws of nature show the way to create

a civil society.

Citizens accept that they have to live together under the

common law, respecting the original contract which creates a sovereign

state with absolute authority.

For Locke (2003), in the State of Nature

(see Yolton (1969), all men are equal and enjoy a freedom without limits.

Unlike Hobbes, Locke, did not believe that men give up to the state all

their rights, but required that they get justice for themselves.

The state

cannot affect the natural rights, lives, properties and conventions of the

Social Contract.

In Two Treatises on Government, he proposed a model

contract which was against the doctrine of divine right and created the

origin of political power as a pact between individuals.

According to

Locke, after creating a political society, the State created a situation in

which the citizens got three things that were missing in the original State

of Nature: laws; judges to adjudicate laws; and the executive power

necessary to enforce these laws.

Rousseau (see Bertram (2003)) has two

distinct theories of Social Contract: the first contains his overview of the

Social Contract; and the second the rules of this Social Contract.

With

respect to the former, Rousseau, in his speech on foundations of origins

of the inequality between men, describes the historical process by which

citizens begin in an original State of Nature, and over time move towards

a civil society.

With his Social Contract Rousseau (1762) outlines a

model of political coexistence within which the individual obeys the law

and yet remains free.

Many would argue that this is impossible – to the

extent that the law, rather than an expression of absolute sovereignty,

instead expresses the general obedience to it.

According to Rousseau, in

the general will, which has as its purpose the interest of the individual

over community, the identity of each is identified with the identity of all.

2.3.

Economic Foundations

In his Theory of Justice, the philosopher Rawls (1971) advances a theory

of a Social Contract at the highest level of abstraction.

His theory argues

against utilitarianism, which requires the measurement and interpersonal

comparison of utilities (happiness or welfare).

The object of the Contract

(see Gauthier (1990)), is not the establishment of political sovereignty,

but a statement of the principles of justice in a well-ordered society.

His

theory of Social Contract follows Kantian lines: rationality requires

respect for individuals and for moral principles that can be justified for

each person.

Its point of departure is an initial position of equality, which

prevents arbitrary factors influencing the moral point of view about the

distribution of benefits and costs of social cooperation.

Acting behind a

4

"veil of ignorance", individuals determine their rights and obligations.

In

contrast, the economist Sen starts with the idea of social progress (Dutta

(2002)), and presents a critique of utilitarianism and the implied theory

of welfare.

In his analysis of inequality, Sen starts with the principle that

the state should not consider only those individuals who have resources.

It must also take into account their ability to use their wealth to choose

their own way of life.

Sen’s theory is built on the concept of functional

capabilities.

Functional capabilities refer to what individuals can achieve

with their resources.

At the descriptive level, this definition of functional

capabilities sees poverty as a deprivation of the ability to survive and not

only as a shortage of income.

At the regulatory level, this idea can be

interpreted as a new basis for the principles of equal and justice.

The

egalitarianism of Sen serves as the principle of equal basic functional

capabilities.

In the field of Social Choice theory, Sen (1972) proposes the

use of interpersonal comparisons of welfare as a way of constructing a

theory of Social Choice.

(It should be noted that Arrow (1963), in his

famous Impossibility Theorem, shows that it is impossible to aggregate

individual preferences into a social preference, if interpersonal

comparisons are not permitted.) According to Sen, using interpersonal

comparisons is the only way to formalize considerations of equal justice.

Giving up these interpersonal comparisons of utility removes the

possibility of taking inequality into account.

2.4.

Norms

In most societies norms of behaviour are observed (see Elster (1989)

and Akerlof (2000)).

A Social Norm is a social rule adopted by a social

group.

The rules....

»

↓↓↓ APERÇU DU DOCUMENT ↓↓↓

Liens utiles

- Oral AMC : How does social media impact American society ?

- What are the influences of the Gilead society and how they have an impact on the woman’s lives?

- Conseil économique et social des Nations unies - relationsinternationales.

- EMC Fragilisation du lien social

- Dialogue social