Comedy I INTRODUCTION Laurel and Hardy Stan Laurel, in overalls, and Oliver Hardy, left, formed one of the most popular comedy teams in motion-picture history.

Publié le 06/12/2021

Extrait du document

Ci-dessous un extrait traitant le sujet : Comedy

I

INTRODUCTION

Laurel and Hardy

Stan Laurel, in overalls, and Oliver Hardy, left, formed one of the most popular comedy teams in motion-picture history.. Ce document contient 1725 mots. Pour le télécharger en entier, envoyez-nous un de vos documents grâce à notre système d’échange gratuit de ressources numériques ou achetez-le pour la modique somme d’un euro symbolique. Cette aide totalement rédigée en format pdf sera utile aux lycéens ou étudiants ayant un devoir à réaliser ou une leçon à approfondir en : Echange

Comedy

I

INTRODUCTION

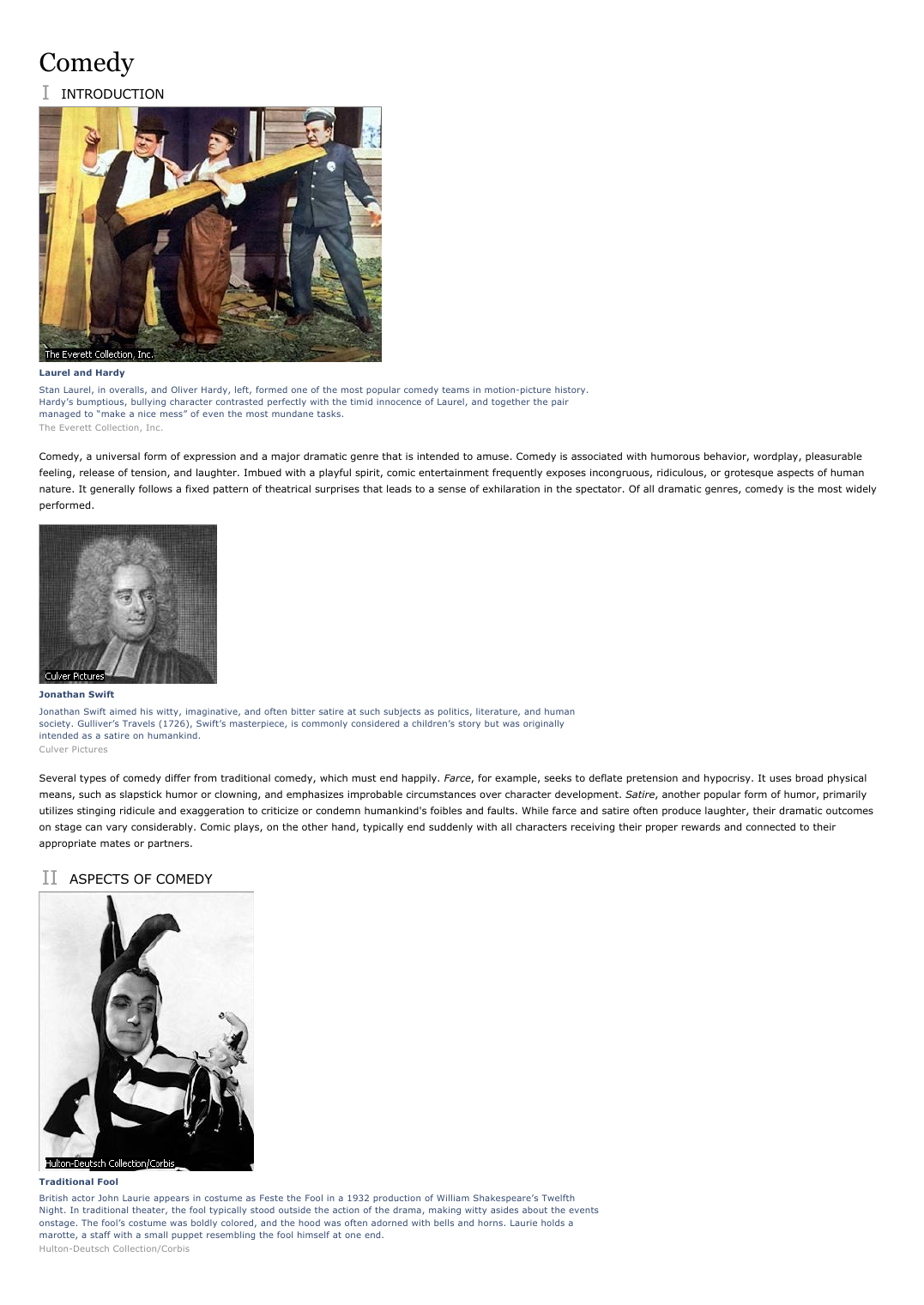

Laurel and Hardy

Stan Laurel, in overalls, and Oliver Hardy, left, formed one of the most popular comedy teams in motion-picture history.

Hardy's bumptious, bullying character contrasted perfectly with the timid innocence of Laurel, and together the pair

managed to "make a nice mess" of even the most mundane tasks.

The Everett Collection, Inc.

Comedy, a universal form of expression and a major dramatic genre that is intended to amuse. Comedy is associated with humorous behavior, wordplay, pleasurable

feeling, release of tension, and laughter. Imbued with a playful spirit, comic entertainment frequently exposes incongruous, ridiculous, or grotesque aspects of human

nature. It generally follows a fixed pattern of theatrical surprises that leads to a sense of exhilaration in the spectator. Of all dramatic genres, comedy is the most widely

performed.

Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift aimed his witty, imaginative, and often bitter satire at such subjects as politics, literature, and human

society. Gulliver's Travels (1726), Swift's masterpiece, is commonly considered a children's story but was originally

intended as a satire on humankind.

Culver Pictures

Several types of comedy differ from traditional comedy, which must end happily. Farce, for example, seeks to deflate pretension and hypocrisy. It uses broad physical

means, such as slapstick humor or clowning, and emphasizes improbable circumstances over character development. Satire, another popular form of humor, primarily

utilizes stinging ridicule and exaggeration to criticize or condemn humankind's foibles and faults. While farce and satire often produce laughter, their dramatic outcomes

on stage can vary considerably. Comic plays, on the other hand, typically end suddenly with all characters receiving their proper rewards and connected to their

appropriate mates or partners.

II

ASPECTS OF COMEDY

Traditional Fool

British actor John Laurie appears in costume as Feste the Fool in a 1932 production of William Shakespeare's Twelfth

Night. In traditional theater, the fool typically stood outside the action of the drama, making witty asides about the events

onstage. The fool's costume was boldly colored, and the hood was often adorned with bells and horns. Laurie holds a

marotte, a staff with a small puppet resembling the fool himself at one end.

Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis

The elements and techniques of comedy are diverse and differ from culture to culture. More than tragedy or serious drama, comic entertainment is controlled by social

conventions that define the boundaries of acceptable humor and topics that are taboo or off-limits for humor. What is considered funny in one place and time may be

forbidden culturally or viewed as infantile or in poor taste in another. Virtually every component of human behavior is subject to comic treatment. This includes bodily

functions, manners, fashion, eating, family quarrels, sexual desire, courtship, the procurement of money and social position, exaggerated violence and punishment,

religious piety, racial and social differences, vain presentations of self, physical shortcomings, cheating and lying, gender reversal, and abnormal fear of aging and

death.

The array of comic techniques and devices in performance are immense. Over-the-top exaggeration and caricature appear at one end of the spectrum, and simple

observation and understatement at the other. Typically, comic productions take advantage of several techniques, both physical and aural. The mainstays of popular

comedy are incongruity (mismatched or illogical placement or juxtaposition), mechanization or bestiality of human behavior, witty repartee, mutual misunderstandings,

slapstick violence, methodical exposure of vanity or deception, and victory of the protagonist (often in the role of the trickster or fool) over a social superior.

III

HISTORY OF COMEDY

Aristophanes

Athenian playwright Aristophanes, who lived from around 448 to 385 bc, wrote satirical comedies that have remained

popular throughout the centuries. Of his more than 40 works, 11 have survived.

Library of Congress

The first written comedies were staged in Athens, Greece, during the 5th century

BC.

Of the dozens of Greek comedies written, only those of the dramatists

Aristophanes and Menander have survived. Staged in the afternoon during an annual winter festival, the plays of Aristophanes were known for their unique blend of

realism (in character), fantasy (in dramatic premise), and obscenity (in language and physical depictions of ribald behavior). Aristophanes's comic universe was peopled

with masked actors who mixed figures from past and present, male and female, divine and mortal, human and animal. With these unnatural interactions and cavortings,

Aristophanes created a giddy theatrical dialogue about life's meaning and other dilemmas of human existence. His Old Comedies--as scholars came to call

them--broadly lampooned the feverish arena of Athenian politics, philosophy, and art of his time. But a declining economic situation and sour political mood soon

dropped a curtain of strict censorship over the classical Athenian theater.

By the 4th century

BC,

a genre known as New Comedy had replaced the harsh cultural critique of Aristophanes. Developed by Menander, the new comedies avoided

topical events and instead created an imaginary world of stereotyped characters, including crafty slaves, impossibly foolish masters, love-struck teenagers, greedy

pimps, and pure-hearted prostitutes. Menander's plots were fueled by the dramatic logic of mistaken identity and coincidence. By the end of a typical Menander play,

each character's destiny became suitably untangled to restore him or her to the proper place in the social alignment.

In the 2nd century

BC,

Roman playwrights Plautus and Terence borrowed heavily from Menander's basic recipe. Writing for a less sophisticated audience, they added

boisterous characters, bawdy subplots, and sharp repartee. Other influences on their productions were Roman mimes, who typically performed risqué routines, and a

southern Italian tradition known as Atellan farce. The mischief of the Greek new comedy was replaced with coy addresses to the Roman spectator and moralizing

prologues. Terence's Latin witticisms, often structured in epigrams (short, pointed sayings), made them a particular favorite of intellectuals more than 1000 years later,

during the Renaissance.

During the Middle Ages (5th century to 15th century), plays featuring saints and biblical stories were popular throughout Europe. These so-called mystery and miracle

plays were performed by local clergy or traveling actors, and they included comic interludes. These humorous episodes inserted into serious biblical narratives or

dramatic histories of saints captivated the illiterate masses. Joseph's confusion over Mary's virgin conception of Jesus Christ, a Jewish spice seller haggling with Jesus's

disciples, and Noah's frustrations with his implacably skeptical spouse were among the situations most often enacted.

Commedia Dell'arte Masks

Masks have been used in theater since the days of Ancient Greece. The masks in this painting are known as half masks.

They were worn by players in the Italian theater form known as commedia dell'arte, which was popular in the 16th

century. The characters portrayed in commedia dell'arte were extremely exaggerated. The masks were designed to

contribute to these exaggerations.

Scala/Art Resource, NY

English playwrights of the 16th and 17th centuries retained much of the medieval blending of comedy and tragedy. Comic inversion and trickery animated historical

dramas and tragedies as well as formal comedies. Unscripted slapstick routines and other devices of low comedy connected the performer to his audiences directly,

much to the irritation of William Shakespeare and other playwrights. Yet, even behind the ornate and elevated language of Shakespeare lay a densely ironic, and

sometimes obscene, wordplay.

Ben Jonson, a contemporary of Shakespeare, provided a practical theory of comedy, derived from his understanding of human physiology and psychology. According to

medical beliefs of his time, four internal liquids, called humors--blood, black bile, yellow bile, and phlegm--determined the health and mental stability of every individual.

When these secretions are in balance, the human body and mind perform in perfect harmony. But when there is an imbalance in the body, the dominant humor creates

an overload of temperament, which was seen the root cause of abnormal behavior and which served, for Jonson, as the origin of comic character. This explanation was

known as the theory of the four humors. Jonson's comedies Every Man in His Humour (1598) and Every Man Out of His Humour (1599) demonstrated this theory

through the eccentricities of the characters.

Commedia dell'arte, an Italian form of improvised comedy popular in the 16th and 17th centuries, also delighted its audiences with its depictions of eccentric types.

Modern comedy emerged from its madhouse of masked characters--the gullible merchant Pantalone, the infantile servant Arlecchino, the vain Captain, the lusty serving

woman Columbine, the idiotic Doctor, and the monstrous rascal Pulcinella. Commedia's dynamic sense of character and madcap plots energized the literary comedies of

Lope de Vega of Spain and Molière of France, as the art form traveled north and west out of Italy.

Commedia also gave British playwrights a fresh and adventurous feeling for erotic themes and contemporary satire. Comedies no longer had to be situated in distant

places or times to achieve their goals. Like Molière, these dramatists found peerless material in the confused and sanctimonious lifestyles of the rising middle class. Their

theatrical parodies and satires were called comedies of manners. During the 18th century sentimental comedies encouraged audiences to uphold virtue and avoid vice,

chiefly by stirring their emotions.

Comic writers of the 19th and early 20th centuries to a large degree followed the successful formats and comic inventions of their predecessors. More popular genres of

stage comedy--such as minstrel shows, vaudeville, burlesques, and musicals--appeared during this period of rapid urbanization and liberated themselves from the

artistic confines and audiences of high dramatic literature. Once again, the ancient arts of clowning and physical comedy were revived in up-to-date modes of

performance (see Clown).

In the first quarter of the 20th century, silent motion-picture comedy developed naturally from these nonliterary sources of low comedy. And the separation of

sophisticated comedy on stage from mass entertainment in radio, sound film, and television accelerated rapidly over the decades. By the 1930s Hollywood, the center of

the film industry, had created an internationally recognized style that harked back to the time-tested techniques and comic types of ancient Greece and Rome.

Following World War II (1939-1945), the United States witnessed the growth of the situation comedy (or sitcom) on television, which featured idealized families dealing

with everyday problems. At the same time black or sick humor became popular in urban nightclubs, with attacks on social mores through shocking language and

offensive imagery in the manner of Aristophanes. In the 1980s and 1990s these two trends merged in unpredictable ways as censorship and the scope of American

taboos greatly diminished.

Contributed By:

Mel Gordon

Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2009. © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

Comedy

I

INTRODUCTION

Laurel and Hardy

Stan Laurel, in overalls, and Oliver Hardy, left, formed one of the most popular comedy teams in motion-picture history.

Hardy's bumptious, bullying character contrasted perfectly with the timid innocence of Laurel, and together the pair

managed to "make a nice mess" of even the most mundane tasks.

The Everett Collection, Inc.

Comedy, a universal form of expression and a major dramatic genre that is intended to amuse. Comedy is associated with humorous behavior, wordplay, pleasurable

feeling, release of tension, and laughter. Imbued with a playful spirit, comic entertainment frequently exposes incongruous, ridiculous, or grotesque aspects of human

nature. It generally follows a fixed pattern of theatrical surprises that leads to a sense of exhilaration in the spectator. Of all dramatic genres, comedy is the most widely

performed.

Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift aimed his witty, imaginative, and often bitter satire at such subjects as politics, literature, and human

society. Gulliver's Travels (1726), Swift's masterpiece, is commonly considered a children's story but was originally

intended as a satire on humankind.

Culver Pictures

Several types of comedy differ from traditional comedy, which must end happily. Farce, for example, seeks to deflate pretension and hypocrisy. It uses broad physical

means, such as slapstick humor or clowning, and emphasizes improbable circumstances over character development. Satire, another popular form of humor, primarily

utilizes stinging ridicule and exaggeration to criticize or condemn humankind's foibles and faults. While farce and satire often produce laughter, their dramatic outcomes

on stage can vary considerably. Comic plays, on the other hand, typically end suddenly with all characters receiving their proper rewards and connected to their

appropriate mates or partners.

II

ASPECTS OF COMEDY

Traditional Fool

British actor John Laurie appears in costume as Feste the Fool in a 1932 production of William Shakespeare's Twelfth

Night. In traditional theater, the fool typically stood outside the action of the drama, making witty asides about the events

onstage. The fool's costume was boldly colored, and the hood was often adorned with bells and horns. Laurie holds a

marotte, a staff with a small puppet resembling the fool himself at one end.

Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis

The elements and techniques of comedy are diverse and differ from culture to culture. More than tragedy or serious drama, comic entertainment is controlled by social

conventions that define the boundaries of acceptable humor and topics that are taboo or off-limits for humor. What is considered funny in one place and time may be

forbidden culturally or viewed as infantile or in poor taste in another. Virtually every component of human behavior is subject to comic treatment. This includes bodily

functions, manners, fashion, eating, family quarrels, sexual desire, courtship, the procurement of money and social position, exaggerated violence and punishment,

religious piety, racial and social differences, vain presentations of self, physical shortcomings, cheating and lying, gender reversal, and abnormal fear of aging and

death.

The array of comic techniques and devices in performance are immense. Over-the-top exaggeration and caricature appear at one end of the spectrum, and simple

observation and understatement at the other. Typically, comic productions take advantage of several techniques, both physical and aural. The mainstays of popular

comedy are incongruity (mismatched or illogical placement or juxtaposition), mechanization or bestiality of human behavior, witty repartee, mutual misunderstandings,

slapstick violence, methodical exposure of vanity or deception, and victory of the protagonist (often in the role of the trickster or fool) over a social superior.

III

HISTORY OF COMEDY

Aristophanes

Athenian playwright Aristophanes, who lived from around 448 to 385 bc, wrote satirical comedies that have remained

popular throughout the centuries. Of his more than 40 works, 11 have survived.

Library of Congress

The first written comedies were staged in Athens, Greece, during the 5th century

BC.

Of the dozens of Greek comedies written, only those of the dramatists

Aristophanes and Menander have survived. Staged in the afternoon during an annual winter festival, the plays of Aristophanes were known for their unique blend of

realism (in character), fantasy (in dramatic premise), and obscenity (in language and physical depictions of ribald behavior). Aristophanes's comic universe was peopled

with masked actors who mixed figures from past and present, male and female, divine and mortal, human and animal. With these unnatural interactions and cavortings,

Aristophanes created a giddy theatrical dialogue about life's meaning and other dilemmas of human existence. His Old Comedies--as scholars came to call

them--broadly lampooned the feverish arena of Athenian politics, philosophy, and art of his time. But a declining economic situation and sour political mood soon

dropped a curtain of strict censorship over the classical Athenian theater.

By the 4th century

BC,

a genre known as New Comedy had replaced the harsh cultural critique of Aristophanes. Developed by Menander, the new comedies avoided

topical events and instead created an imaginary world of stereotyped characters, including crafty slaves, impossibly foolish masters, love-struck teenagers, greedy

pimps, and pure-hearted prostitutes. Menander's plots were fueled by the dramatic logic of mistaken identity and coincidence. By the end of a typical Menander play,

each character's destiny became suitably untangled to restore him or her to the proper place in the social alignment.

In the 2nd century

BC,

Roman playwrights Plautus and Terence borrowed heavily from Menander's basic recipe. Writing for a less sophisticated audience, they added

boisterous characters, bawdy subplots, and sharp repartee. Other influences on their productions were Roman mimes, who typically performed risqué routines, and a

southern Italian tradition known as Atellan farce. The mischief of the Greek new comedy was replaced with coy addresses to the Roman spectator and moralizing

prologues. Terence's Latin witticisms, often structured in epigrams (short, pointed sayings), made them a particular favorite of intellectuals more than 1000 years later,

during the Renaissance.

During the Middle Ages (5th century to 15th century), plays featuring saints and biblical stories were popular throughout Europe. These so-called mystery and miracle

plays were performed by local clergy or traveling actors, and they included comic interludes. These humorous episodes inserted into serious biblical narratives or

dramatic histories of saints captivated the illiterate masses. Joseph's confusion over Mary's virgin conception of Jesus Christ, a Jewish spice seller haggling with Jesus's

disciples, and Noah's frustrations with his implacably skeptical spouse were among the situations most often enacted.

Commedia Dell'arte Masks

Masks have been used in theater since the days of Ancient Greece. The masks in this painting are known as half masks.

They were worn by players in the Italian theater form known as commedia dell'arte, which was popular in the 16th

century. The characters portrayed in commedia dell'arte were extremely exaggerated. The masks were designed to

contribute to these exaggerations.

Scala/Art Resource, NY

English playwrights of the 16th and 17th centuries retained much of the medieval blending of comedy and tragedy. Comic inversion and trickery animated historical

dramas and tragedies as well as formal comedies. Unscripted slapstick routines and other devices of low comedy connected the performer to his audiences directly,

much to the irritation of William Shakespeare and other playwrights. Yet, even behind the ornate and elevated language of Shakespeare lay a densely ironic, and

sometimes obscene, wordplay.

Ben Jonson, a contemporary of Shakespeare, provided a practical theory of comedy, derived from his understanding of human physiology and psychology. According to

medical beliefs of his time, four internal liquids, called humors--blood, black bile, yellow bile, and phlegm--determined the health and mental stability of every individual.

When these secretions are in balance, the human body and mind perform in perfect harmony. But when there is an imbalance in the body, the dominant humor creates

an overload of temperament, which was seen the root cause of abnormal behavior and which served, for Jonson, as the origin of comic character. This explanation was

known as the theory of the four humors. Jonson's comedies Every Man in His Humour (1598) and Every Man Out of His Humour (1599) demonstrated this theory

through the eccentricities of the characters.

Commedia dell'arte, an Italian form of improvised comedy popular in the 16th and 17th centuries, also delighted its audiences with its depictions of eccentric types.

Modern comedy emerged from its madhouse of masked characters--the gullible merchant Pantalone, the infantile servant Arlecchino, the vain Captain, the lusty serving

woman Columbine, the idiotic Doctor, and the monstrous rascal Pulcinella. Commedia's dynamic sense of character and madcap plots energized the literary comedies of

Lope de Vega of Spain and Molière of France, as the art form traveled north and west out of Italy.

Commedia also gave British playwrights a fresh and adventurous feeling for erotic themes and contemporary satire. Comedies no longer had to be situated in distant

places or times to achieve their goals. Like Molière, these dramatists found peerless material in the confused and sanctimonious lifestyles of the rising middle class. Their

theatrical parodies and satires were called comedies of manners. During the 18th century sentimental comedies encouraged audiences to uphold virtue and avoid vice,

chiefly by stirring their emotions.

Comic writers of the 19th and early 20th centuries to a large degree followed the successful formats and comic inventions of their predecessors. More popular genres of

stage comedy--such as minstrel shows, vaudeville, burlesques, and musicals--appeared during this period of rapid urbanization and liberated themselves from the

artistic confines and audiences of high dramatic literature. Once again, the ancient arts of clowning and physical comedy were revived in up-to-date modes of

performance (see Clown).

In the first quarter of the 20th century, silent motion-picture comedy developed naturally from these nonliterary sources of low comedy. And the separation of

sophisticated comedy on stage from mass entertainment in radio, sound film, and television accelerated rapidly over the decades. By the 1930s Hollywood, the center of

the film industry, had created an internationally recognized style that harked back to the time-tested techniques and comic types of ancient Greece and Rome.

Following World War II (1939-1945), the United States witnessed the growth of the situation comedy (or sitcom) on television, which featured idealized families dealing

with everyday problems. At the same time black or sick humor became popular in urban nightclubs, with attacks on social mores through shocking language and

offensive imagery in the manner of Aristophanes. In the 1980s and 1990s these two trends merged in unpredictable ways as censorship and the scope of American

taboos greatly diminished.

Contributed By:

Mel Gordon

Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2009. © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

↓↓↓ APERÇU DU DOCUMENT ↓↓↓

Liens utiles

- George Washington I INTRODUCTION George Washington (1732-1799), first president of the United States (1789-1797) and one of the most important leaders in United States history.

- Isaac Newton I INTRODUCTION Isaac Newton (1642-1727), English physicist, mathematician, and natural philosopher, considered one of the most important scientists of all time.

- Film Noir I INTRODUCTION Lynch's Blue Velvet The motion picture Blue Velvet (1986) brought wide acclaim to American director David Lynch.

- Metalwork I INTRODUCTION Metalwork, in the fine arts, objects of artistic, decorative, and utilitarian value made of one or more kinds of metal--from precious to base--fashioned by either casting, hammering, or joining or a combination of these techniques.

- Gothic Art and Architecture I INTRODUCTION Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris Notre Dame Cathedral, in Paris, was begun in 1163 and completed for the most part in 1250.